Rethinking Hospitalization for Possible Serious Bacterial Infections in Young Infants: Evidence from Pakistan to Inform National Guidelines

Livestreaming April 26, 2025 11am to 1pm:

LINK

Context

Neonatal infections remain a major cause of preventable deaths in Pakistan. Despite WHO guidelines recommending hospital-based injectable antibiotic treatment for all cases of Possible Serious Bacterial Infection (PSBI), access to hospitals remains limited, especially for low-income and peri-urban/rural families. Hospitalization also carries risks of nosocomial infections, particularly in overburdened public sector facilities.

Two large multicountry randomized controlled trials (RCTs) coordinated by WHO and conducted across Africa and Asia evaluated the safety and efficacy of outpatient antibiotic regimens for young infants presenting with:

- A single low-mortality-risk sign (e.g., fever, fast breathing in infants <7 days, or severe chest indrawing) – RCT1

- One moderate-risk or multiple low-risk signs – RCT2

NOTE: Infants with critical illness were not eligible and hence results will not apply to the critically ill babies.

Together, these trials included over 12,000 infants and offer strong, pragmatic evidence to support a revision of PSBI management guidelines, particularly for outpatient care.

Pakistan Participation in the Trials

Pakistan was a key site in the trials. The trials were conducted in Karachi at four hospitals, including Sindh Government Children Hospital (SGCH), National Institute of Child Health (NICH), The Aga Khan Hospital for Women and Children, Kharadar (AKU-KH) and Sindh Institute of Child Health and Neonatology (SICHN). The trials enrolled over 2,000 Pakistani infants, contributing significantly to the global sample of 12,000+.

Pakistan was a key site in the trials. The trials were conducted in Karachi at four hospitals, including Sindh Government Children Hospital (SGCH), National Institute of Child Health (NICH), The Aga Khan Hospital for Women and Children, Kharadar (AKU-KH) and Sindh Institute of Child Health and Neonatology (SICHN). The trials enrolled over 2,000 Pakistani infants, contributing significantly to the global sample of 12,000+.

Trial Designs and Interventions

1. RCT 1 - Direct Outpatient vs Inpatient Treatment for Single Low-Mortality-Risk PSBI Signs

- Eligibility: Infants with one low risk sign only (e.g., fever ≥38°C, fast breathing <7 days old, or chest indrawing)

- Intervention:

- Outpatient arm: Injectable gentamicin (2 days) + oral amoxicillin (7 days)

- Inpatient arm: Injectable gentamicin + ampicillin for 7 days

- Setting: Randomized at first contact, no CRP testing

- Goal: Evaluate whether direct outpatient care is as safe as inpatient care

2. RCT 2 - CRP-Guided Antibiotic Switch for Moderate-Risk or Multiple Low-Risk Signs

- Eligibility: Infants with moderate-risk (e.g., not feeding well, low temp <35.5°C, movement only on stimulation) or multiple low-risk signs

- Intervention:

- All infants started on inpatient care with ampicillin + gentamicin. At 48 hours, those clinically stable + CRP negative were randomized to:

- Outpatient switch group: Discharged on oral amoxicillin (5 more days)

- Continued inpatient group: Full 7-day injectable treatment

- Goal: Test early step-down to outpatient care based on CRP results and clinical reassessment

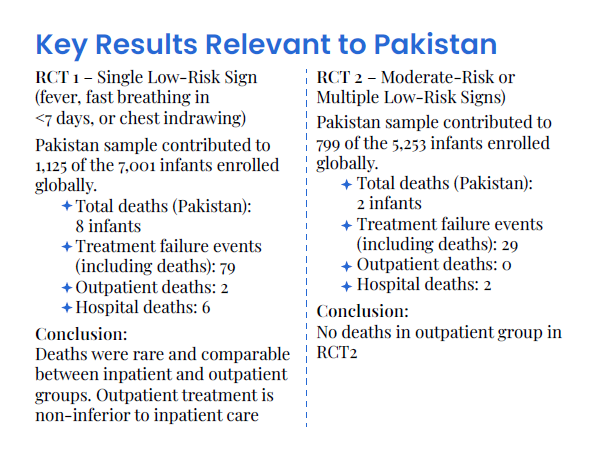

Key Results Relevant to Pakistan

1. RCT1 – Single Low-Risk Sign (e.g., fever, fast breathing in <7 days)

Pakistan sample contributed to 7,001 of the enrolled infants globally.

- Total deaths (all sites): 32 infants

- Treatment failure events (including deaths): 36

- Outpatient deaths: included in the 7.7% poor outcome

- Hospital deaths: included in the 7.8% poor outcome

Conclusion: Deaths were rare and comparable between inpatient and outpatient groups. Outpatient treatment is non-inferior to inpatient care (p < 0.01)

2. RCT2 – Moderate-Risk or Multiple Low-Risk Signs

Pakistan enrolled a significant subset of the 5,253 infants globally.

- Total deaths (all sites): 14 infants

- All 14 deaths were classified as treatment failures

- Outpatient group poor outcome (incl. deaths): 4.4%

- Inpatient group poor outcome (incl. deaths): 3.7%

Conclusion: Again, no increased mortality in outpatient group

Additional Insights from Pakistan Sites

- High adherence to treatment protocols

- 95% received complete outpatient regimens (gentamicin + amoxicillin)

- Low rates of severe adverse events

- Comparable or lower mortality in outpatient arms

- Strong follow-up infrastructure implemented with CHWs and mobile health tools

Why This Matters for Pakistan

- Referral acceptance is low: Many families in Pakistan decline hospital referral due to cost, distance, or gender/social barriers.

- Hospital overcrowding: Tertiary hospitals are overwhelmed and not always equipped for infection prevention.

- Primary care is underused: The Lady Health Worker (LHW) program and secondary hospitals could offer decentralized outpatient PSBI care.

- It cost Rs2,000 to treat such children at home and Rs18,000 at a hospital.

Policy Recommendations for Pakistan

Update national and provincial PSBI treatment guidelines to allow outpatient care for:

- Infants with a single low-mortality-risk sign

- Infants with moderate-risk or multiple low-risk signs

Enable outpatient antibiotic protocols at secondary hospitals, urban health centers, and BHUs

Leverage LHWs and frontline providers to support referral, follow-up, and family counseling

Train primary care physicians and nurses on the outpatient PSBI regimen

Ensure availability of dispersible amoxicillin and gentamicin injection in the MNCH supply chain

Institutionalize follow-up systems using community-based and mHealth-supported approaches

What's Next for Implementation in Pakistan?

- Use AKU and government trial learnings to pilot outpatient PSBI management in provinces

- Integrate updated protocols into IMNCI training and supervision

- Disseminate evidence through PMDC-accredited CME sessions, the Pakistan Paediatric Association, and District Health Office (DHO) networks

- Advocate for PC-1 inclusions to support training, drugs, and follow-up capacity

Conclusion

Pakistan now has local evidence that outpatient care for select PSBI cases is safe, effective, and feasible. With careful implementation, this approach can significantly expand access to life-saving treatment, reduce newborn mortality, and strengthen primary care-based newborn services.

Prof. Fyezah Jehan

Chair, Department of Paediatrics & Child Health

Aga Khan University

Resources:

WHO guidelines