We need precision medicine to target the world's most vulnerable children: Dr Judd Walson

Dr Judd Walson, the chair of International Health, at the Bloomberg School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins University, delivered the keynote speech at the inauguration of the fifth Research Week of the Department of Paediatrics & Child Health, AKU on September 1, 2023. The following is a lightly edited transcript.

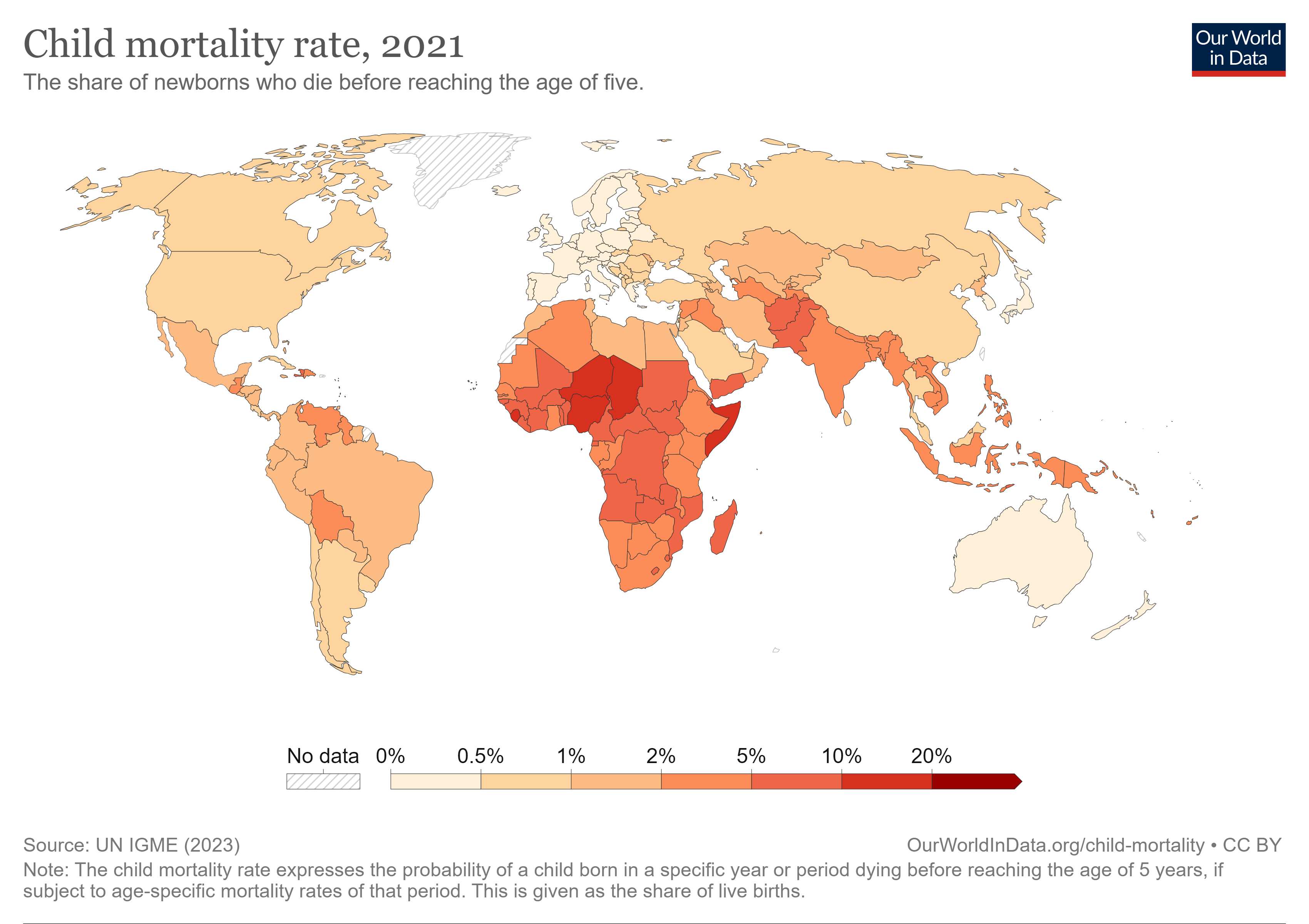

I want to start out by reiterating the incredible gains over the past several decades in child and maternal mortality. But if we zoom out and look at the impact that we've been able to have on child mortality, it's quite striking. That small change that we've seen over the last 30 or 40 years pales in comparison to the changes in mortality over the last hundreds and thousands of years.

In the words of Hans Rosling, while things may be bad, they're getting better. I think that's a message of hope. But it appears as though residual mortality still remains much harder to address. We need new thought about how we're going to target children at the highest risk in order to continue to reduce mortality.

There's a striking association between rates of child mortality globally and indicators of poverty. If we look at the share of the population in countries living in extreme poverty, and we plot that against where the mortality rate is for a variety of countries, there is this incredible distribution which you can see here with almost all of the high mortality occurring in areas of very significant extreme poverty.

One thing that's clear, and I think has been embraced by the Pediatrics department and the research done at your institution, is moving beyond this pure biomedical approach to understanding what interventions need to be put in place to target some of these underlying drivers of mortality.

Future direction of pediatric research?

We're at an inflection point in thinking about how we target the most vulnerable. When there were many people dying in communities, empiric syndrome-based interventions just laid out interventions across whole populations and were a relatively efficient way of ensuring that those in need received necessary intervention.

As the numbers continue to decline, we need to be smarter. We need to target children where we can have the biggest impact. How do we start to think about novel interventions and platforms that can deliver these? It's important to recognize that governments don't implement interventions. They implement programs that implement interventions. We also need to understand what are the mechanisms that drive this so that we can target interventions based on biology but also on underlying social and other factors which can be optimized to reduce mortality.

Three key areas where we can move for the future of research in this space.

i) We need to move towards a more risk stratified approach to address the most vulnerable. Ii) There are just incredible advancements in data science and technology that are allowing us to do things with existing data that we never thought possible.

iii) We have to reexamine our roles and responsibilities in the global health space. Where is power centered? Who's making decisions and who's at the table?

Oftentimes we present estimates at the national or regional levels. But that masks the incredible heterogeneity underlying that. You can plot changes in underlying mortality risk across countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Even within those countries, there's quite a lot of diversity.

Interventions and coverage

Often, what you see is that those in greatest need, those who are most vulnerable, are often achieving incredibly low coverage, even when national estimates are reporting relatively high coverage across populations.

When we do have very narrow ranges for some specific interventions, it tends to mean that the overall coverage is very, very low. The higher the coverage you get, the bigger that range becomes. That highlights how much we're leaving behind the most vulnerable in our interventional approaches.

I think we need to move away from this sort of empiric population-based approach of many public health interventions towards a more targeted or risk-stratified care. This is continuing on a spectrum of individualized medicine, precision medicine.

CHAIN, or the Childhood Acute Illness Nutrition Network

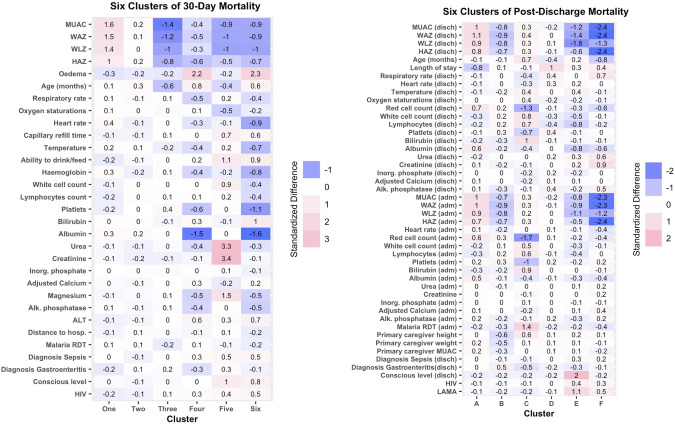

CAPTION: Phenotypes of 30-day and post-discharge mortality. Credit: The Lancet

We worked very closely with collaborators in Pakistan, the AKU, and Civil Hospital, Karachi on this study. It is focused on understanding mechanisms of risk in children presenting for care for acute illness in low- and middle-income countries.

We knew the presence of low anthropometry, or being malnourished, having young age and being acutely ill, are three features highly associated with mortality. The challenge with this is that young age is not a modifiable risk factor.

We have many interventions for acute illness in the hospital setting, but we know that even applying those 100% doesn't get us all the way to reducing risk.

This study was conducted across a number of sites in Asia and South Saharan Africa with the idea if we ensure that WHO-adherent guidelines are being followed in inpatient settings, and we follow children through their hospitalization and then out six months after they go home, are we able to understand better those pathways leading to mortality?

The children were enrolled at admission to hospital for an acute illness, and followed through their hospitalization, up to 180 days. We collected an enormous amount of both biological samples and other data and looked at a whole host of features.

We enrolled a little over 3,100 children across a whole range of nutritional strata, including those who are severely malnourished. Not unsurprisingly, we found very high mortality, among those who were severely wasted. Even among those who were normally nourished and receiving guideline adhering care, they had about 4% mortality, which is still unacceptably high.

While there was a much higher degree of mortality in the early time points associated with that period of being in hospital, (median time of hospitalization about four days), over half of all the mortality occurred

after that. Almost half of all mortality happened after children were discharged. I think many of us as clinicians feel that discharge happens when we feel children are at least well on the road to recovery. But the data show us across all the sites, and it was very consistent, and across all the nutritional strata, was that children are being discharged at considerable residual risk of mortality.

In this cohort, we collected an enormous amount of biological samples, and we're working with laboratories around the world to look at the microbiome, the metabolome, the lipidome, micronucleotide assays, energy metabolism, microbiology. We're working with a group at Stanford to synthesize the data into a large systems biological model that can map biological pathways underpinning death.

This highlights using an integrated multi-omics approach, so we're able to look at specific pathways underlying death that separate out populations based on this complexity of data.

We see children who look clinically healthy and their labs tell us they're healthy. But we can also find discrete groups of children who look clinically healthy, but who are biologically not, or vice versa. When we plot it, we find distinct populations, which enables us to define features that enable us to find the children, for example, who don't necessarily look clinically ill, but biologically are very, very clearly at risk.

With data science and the Wellcome Sanger Institute, we've been able to expand the genomic sequences of one particular species of gut bacteria associated with growth: Infantis. There's clustering and stratification of these strains by geography. There's a number of interventions now moving forward in the microbiome space targeting things like B. infantis supplementation or alteration of B. infantis and other bacteria. If we're using strains that were not mapped to the right geography, we may be much less likely to be affected.

Power imbalances

Maybe the biggest area of future development is to re-examine how global health gets done. We're at an incredible inflection point where people are recognizing the incredible power imbalances in how decision-making is happening in this space, and then the need to re-examine how institutions in Europe and the United States are engaged in the global health space.

How do we redefine these roles and responsibilities of our institutions? And how do we find actionable ways to address some of the impacts of colonialism and power imbalances that historically not only led to the health disparities that we're trying to address, but have led to failures in the response to our ability to affect those disparities.

When we have strong bi-directional institutional partnerships, such as I've been fortunate to have with AKU, I think these are the types of partnerships where these difficult conversations can happen because of a real foundation of trust.

How do we recenter the research and the decision-making around research to institutions that are based within low- and middle-income settings and away from that sort of decision-making happening in the global north and then being sort of pushed on institutions in the global south.

I think that we have to think about partnership differently. When institutions in the US control the resources, we can be the kind of partner we want to be, because ultimately others are dependent on those resources flowing from us.

But I see that in the next 10 to 20 years, more and more resources are moving towards institutions in low- and middle-income countries, and institutions with the capacity to manage them, such as AKU… that's excellent. That's exactly what should be happening. But that means that our ability to be an effective partner now is not being judged by ourselves, but by the partner who controls the resources.

As I move into this role in Johns Hopkins, I think we need to think what does it mean to be a preferred partner? How do we ensure that we're being the kind of partner institutions that work with us want to see, so that we continue to be a partner that's sought out for the expertise that I hope we can continue to bring.