Success story: sharing the Ps model for virtual teaching during COVID pandemic

This story is written by Shanaz Cassum, Amina Aijaz, Khairunissa Mansoor, Amina Hirji, & Amber David, from School of Nursing and Midwifery, Pakistan.

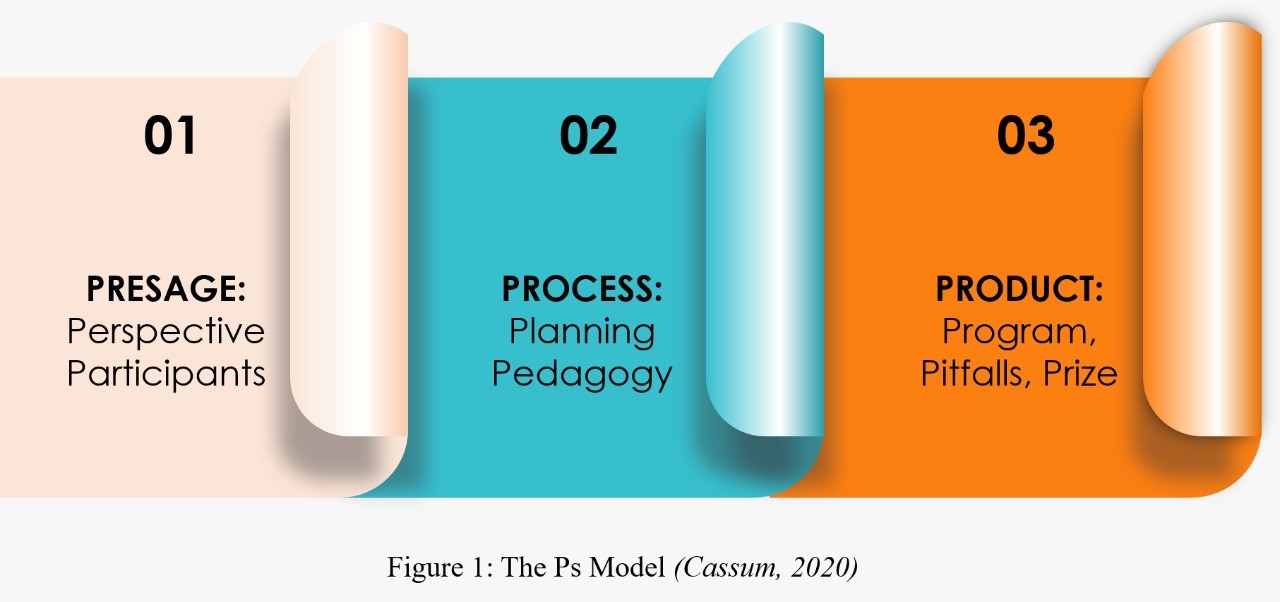

With the COVID-19 pandemic hitting Pakistan in March 2020, the routine university activities of classroom teaching, meetings, research work were severely hindered. Everyone had to think of ways of working from home via zoom meetings for online teaching or offering telehealth services to enable the business to continue during this social distancing era. Faculty at the School of Nursing and Midwifery (SONAM) in Karachi also started thinking of how to initiate online teaching. Every year, a face to face module for Palliative Care and End of Life is offered to Trainee Nurse Interns (TNIs), but due to the COVID – 19 pandemic lockdown leading to a temporary closure of schools, this module was offered on an online mode. Biggs 3Ps model of teaching and learning was our guide during this transformation. However, we creatively expanded the Ps in the model based on our contextual experience of planning and programming an online module. The Ps Model created (Figure 1) became our framework, as it outlined the additional P variables that must be kept in mind for innovating a teaching-learning endeavour.

The adapted model has three phases. The first phase Presage refers to the characteristics of the learner and the learning environment (Ingrid, 2014). Our Presage indicator began in March 2020, when the COVID - 19 pandemics reached Pakistan, and the government announced the closure of schools and offices and advised that people should work from home, and teachers to start online teaching. What were our perspectives? As part of the internship curriculum, trainee nurse interns (TNIs) who are recent graduates of a four-year degree program, had to be offered a Palliative and End of life care module, via face to face classes and simulation-based activities at the Centre for Innovation in Medical Education (CIME) laboratory with high fidelity simulators. However, this was not possible due to the lockdown phenomenon during the pandemic. The participants, both teachers and learners, were observing social distancing and working/studying from home. The presage was favoured by the fact that learners had the experience of using VLE as a blended modality, and the teachers were expert in developing hybrid modules on HTML 5 Package, on MOODLE (VLE) which ignited our desire to transit to online teaching.

The second phase Process refers to the creation and execution of various study processes to make learning meaningful (Ingrid 2014). Our processes started with virtual planning meetings, whereby we discussed objectives and ways of transforming the conventional module into a blended online module. We met with the e-learning coordinator and sought help with preparing the digital resources required such as voice-over PowerPoint and creating lecture videos. We decided to use a blend of teaching pedagogies; online quizzes, reflective writing, virtual seminar, discussion board, virtual simulation and live online classes using Microsoft Teams software. As the university had a license for using the Microsoft Teams (MT) software, we got a short informal training on using MT for conducting synchronous live classes. Our goal was to create a learning package that would allow the participants to engage with peers, the content and the faculty, synchronously and asynchronously and promote deeper learning.

The last phase Product refers to the performance outcomes and the productivity of learning of the students (Ingrid, 2014). Our last phase, Product, began, when our program was uploaded on MOODLE and the TNIs were sent an official email, with the URL link, and a password, so they could enrol, access and review the H5P module on the course site, prior to the starting date. The performance began, when on day one, 141 TNIs came online, as scheduled, and joined the live synchronous class. We gave them a virtual tour of the course site and reviewed the module objectives, expectations, and the activities to complete during the week-long module. This helped the learners not only to be organized but also allowed them to manage their overall learning activities and monitor their own performance. We met them on Microsoft Teams, in a large class (LCF) where all TNIs attended the faculty lecture, as well as in seven small teams for group discussions and simulation activity, with a teacher-student ratio of 1:20. The pitfalls we faced, were unique and challenging. Three TNIs could not join, as they were on earned leave, and had gone home to the Northern Areas of Pakistan during the lockdown, and could not connect virtually due to poor internet connectivity. About 10% of Karachi based TNIs also experienced electricity shutdown and therefore had internet connectivity issues. However, they were able to access the VLE course materials and attend online classes via smartphones 3G mobile data package, which they claimed to find expensive. These TNIs were also intermittently present in the online classes and were sent live class recordings to supplement their learning. The prize for this online endeavour was achieved when the TNIs achieved the learning outcomes and completed the expected learning activities. They attempted an online test from their own homes or hostels via the VLE system, and the scores ranged between 61%-95%. In the test, the questions and responses were shuffled to negate discussions with peers via phone calls since the test was time-bound. The multiple-choice questions were marked automatically and the faculty graded the short answers manually from the online site and after reviewing the item analysis, the results were shared with the TNIs, at the click of a few buttons. The written feedback from interns was very encouraging. Many shared that they felt more responsible for doing required readings, and completing activities on time, as faculty were not taking classes in the usual manner. Some even mentioned that they studied for more than eight hours a day, watching videos and reviewing articles and PowerPoint as they found it quite interesting and useful; some found it exhausting to sit in front of their computers for long hours. Some shared that the reflection and virtual simulation were reality-oriented and helpful, whereas others felt that online guided imagery did not trigger them as much as in face to face class. Some TNI shared that their motivation to study online was less due to COVID stress, whereas few felt it was a good diversion during the lockdown. TNIs appreciated the faculty's efforts of putting together the online module for them despite social distancing, as they were missed interacting with their friends and peers. Many TNIs commented that the module was very intensive and suggested that we increase its duration and spread it over two-three weeks, as it was difficult for them to study from home while participating in household chores during the lockdown.

Overall it was a victorious endeavour for the teaching team involved despite the challenging hitches encountered. Similar models of innovative eLearning must be developed to provide insight on student engagement, supporting student learning post lockdown, and assisting faculty and students to use flexible and innovative pedagogy and transit to virtual online learning successfully.

Reference

Ingrid del Valle García Carreño, (2014). Theory of Connectivity as an Emergent Solution to Innovative Learning Strategies. American Journal of Educational Research, 2(2): 107-116. doi: 10.12691/education-2-2-7.